Two floors of the human powered student building are dedicated to washing clothes and showering — the individual student rooms have no bathrooms or washing machines.

Showering and washing clothes both involve the use of hot water, which requires a lot of human power. To make it work, the student community applies low-tech and lifestyle changes.

Showering

The energy use of hot showers mainly consists of heating the water. The Netherlands has little sun, which makes solar thermal boilers less suitable, especially during the times of the year when hot showers are most needed. Furthermore, a tower building has not enough roof space to provide hot water in this way.

The use of wood fires to produce hot water is not possible either because of the strict fire and health regulations on campus, and because we aim to be self-sufficient in terms of energy production. Because the biogas plant only supplies enough thermal energy for cooking, there’s no other option than to use human generated electricity to provide hot water for showering, a very energy-inefficient process.

Energy Use of a Hot Shower

A seven minute shower using a low flow shower head (6 litres of water per minute) requires 1.5 kWh of electricity, assuming the temperature of the water is raised from 10°C to 40°C. Consequently, one student taking a seven minute shower involves a workforce of 15 students generating power for one hour, assuming each of them can produce 100 watts.

The energy consumption of a shower can be lowered by one third through the use of a heat exchanger, which recovers waste heat from the shower drain. This brings the energy needs down to 1 kWh of electricity per 7-minute shower, for which we need “only” ten people generating power for an hour.

The Hot Shower Paradox

Consequently, providing 750 students with one hot shower per day would require a workforce of 750 students generating power for 10 hours per day. In other words, we need the complete student population working all day to provide everyone with a hot shower. This makes no sense.

How to solve this? First, hot showers are limited to 3 minutes, while the temperature is lowered to 37°C. This brings the energy use of a hot shower with heat exchanger down to 0.4 kWh. Consequently, four students need to work out for 1 hour to provide another student with a 3-minute hot shower.

Although shorter and slightly cooler showers reduce energy consumption substantially, providing all 750 students with one hot shower per day would still require a workforce of 375 students — half the population — exercising for 8 hours per day.

If the working half of the student population then decides to take a hot shower themselves, the freshly showered other half would need to produce power and get sweaty again. In other words, the student population ends up in a never ending spiral of showering and producing power for showering.

Solving the Hot Shower Paradox

This paradox is solved in several ways. First, people who provide energy for the hot showers of others are only allowed to take cold showers after their work shift. This is feasible, because these students would be so hot after their efforts that they can endure (and probably long for) a cold shower. Cold showering takes place in the receiving reservoir of the hydraulic system of the building, which is located on the communal energy producing floors.

Second, students are only allowed to take a hot shower every three days. This means that we need energy for only 250 hot showers per day, which can be provided by a workforce of 125 students exercising 8 hours per day. In other words, one-sixth of the student population is needed to provide energy for daily showering.

This doesn’t mean that the students will smell bad. They are encouraged to do more quick washes at the sink, just like in the old days, or to take cold showers. Again, this is possible because all students will need to produce energy daily for a variety of reasons, raising their body temperature and lowering their need for hot showers.

Peak Demand & Water Pressure

An additional difficulty is that most students want hot showers in the mornings and in the evenings, which could lead to large peak power demand. This is solved in two ways. First, the number of showers is limited to twenty for the whole building, distributed over two floors. This limits the maximum power use at any moment to 8 kW.

Second, the generated energy is stored in the gravity batteries in the former elevator shafts, which means that energy production and energy use should not happen simultaneously.

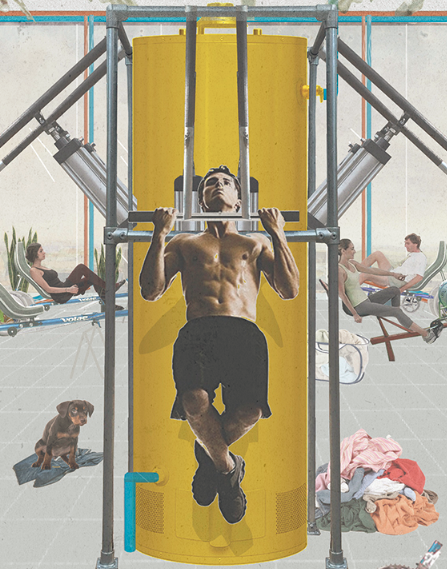

Finally, showering also requires energy to provide water under pressure. Piped water is pumped to the shower floors using energy from the communal power producing floors. However, to provide the additional pressure that’s needed to operate the showers, every student needs to do a quick workout before taking a shower (hot or cold), pumping water into a small hydraulic accumulator that is located in between the showers.

Energy Use of a Laundry Machine

Because the number of showers is small, there’s enough space left for doing the laundry. A modern energy efficient washing machine that can hold 9.5 kg of clothes uses roughly 500 watts of power. Based on guidelines for student communities, we need roughly 30 such washing machines for 750 students.

Operating all these machines simultaneously would require 15 kW of electric power, which corresponds to the power production of roughly 150 students (assuming they are each producing 100W). Operating one washing machines requires five students generating power.

Wool & Cold Water

However, this energy use can be lowered substantially. First of all, students are advised to wash their clothes with cold water. In recent years, manufacturers have found ways to create detergents that work very well in cold water. Furthermore, the students are advised to wear woolen clothing, which needs to be washed less often and preferably in cold water.

Between 80 and 90% of the energy use of a washing machine is used to heat the water, which leaves roughly 75 watt of electric power for the mechanical movement of the machine. Washing clothes in cold water thus lowers the power requirements of the 30 washing machines from 15 kW to 2.2 kW, for which we need only 22 students.

Mechanical Power Transmission

However, instead of generating electric power on the communal power floors and then distributing it to the washing machines, we make use of a direct mechanical power transmission and opted for a variety of human powered washing machines.

This lowers energy use even further (we avoid substantial energy conversion losses in electric generators and motors) and makes it possible to power the machines on the spot. Consequently, students can generate the energy to wash their clothes themselves.

However, the communal laundry space offers further possibilities for reducing energy use. Two or more students can fit their laundry into one machine, and shorten their power producing time.

For washing really dirty clothes, students still have the option to use hot water. However, this will cost them extra power generation duty.

Clothes Drying

Clothes drying, the biggest energy user in a laundry room, happens in the most traditional way: students hang their clothes to dry on racks fixed to their windows.

This will give a Mediterranean touch to the Van Unnik student building. Heavy duty clothespins are provided to withstand the strong winds in the Netherlands.

Leave a reply to Mathias Cancel reply